An astute reader, always with the best interests of this newsletter in mind, mentioned disappointment that my last post about systems mapping Congress did not include much of the actual map. Although my team made only set of revisions from our first draft circa 2016, I think it holds up well to the current setting of the 119th Congress. If you are a reader who’s new to the congressional scene or systems thinking about a living institution, this post is for you.

I’m writing during the first full-blown constitutional crisis of this new presidential administration, which at first glance is the most serious of my lifetime (I was born during the Carter Administration). The White House, by pausing all federal grant payouts, is overturning the inherent power of Congress to direct what the federal government spends money on. I expect many in the majority party in the House and Senate to say this is well and good in the coming days. I think the map speaks to some of this moment of breakdown between the separation of powers.

It’s also a moment to think about what we missed in what really was happening to federal-level politics. You’ll see the word “partisan” in some form all over the map. It was designed with the problem of partisan polarization, and the system’s struggles to contend with its intensity, in mind. These were, in the language of systems thinking, “stuck factors” we had to work around and find leverage elsewhere to get things moving again. Reading the map again now, with its core story of intense, cyclical frustration in Congress’ inability to both function and satisfy the public, I can see how we weren’t quite ready to accept the potential that members would choose to accept subversion of the constitutional order to achieve the level of political control necessary for their policy ends. That was the situation on January 6, 2021, and it appears to be it now. The immediate need for democracy reformers now, therefore, is to prioritize this divide between those committed to constitutional order and those who are … something else … and to de-legitimize that faction as democratic actors.

Walking through the core stories

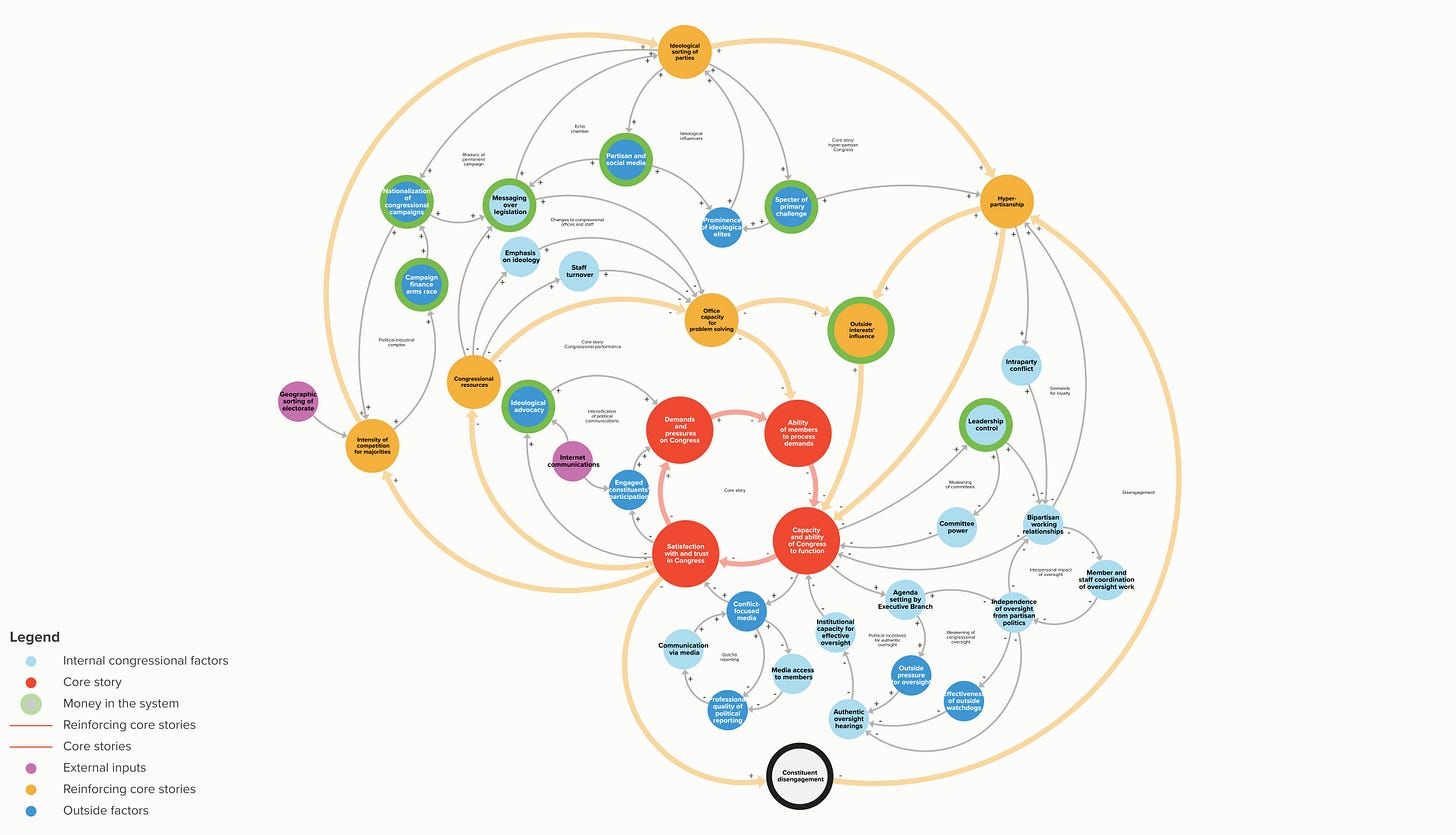

The best way to explore the systems map is on the Kumu platform, which we used to construct it. It allows users to zoom around the map, isolate loops, and read much longer narratives I wrote during its launch. For those who really want to strain their eyes, here’s the map in full, legend included.

The real power of the map is to see how distinct narratives about congressional function intersect and interact, often to make some institutional factors get worse in tandem (for example, bipartisan working relationships or “office capacity for problem solving.”) Depending on the factor, its role in lots of different narratives can indicate something that’s really difficult to change or something with significant leverage if addressed. It’s really hard, for example, to change all the things about members’ decision making to make bipartisan working relationships more positive.

Let’s skip to the key insights on the map:

The red core story loop is our deeper understanding of the modern Congress in peril: many things being asked of it in a complex society, a difficulty in processing those demands, and therefore a breakdown in its ability to function in a productive or satisfying way for the public. It think that’s a pretty solid, pithy explanation for why people feel like the institution isn’t working — it’s asked to solve problems, but doesn’t deliver.

This time in congressional history, however, isn’t particularly unique for congressional inaction or dysfunction. Any cursory knowledge of American political history reveals that Congress has sucked before. What is unique about our era is in gold (and these colors are just design choices): the unusually close and intense competition for majorities in both the House and Senate. I was influenced by Frances Lee’s book Insecure Majorities here, which argues that we see hyper-partisan behavior in Congress because both parties are just trying to score points in preparation for the next election, which often could decide the majority in contrast to periods of weaker partisan electoral competition. We plop in the middle of this argument the observation that the parties have become more ideologically sorted, which is to say they have realigned in ways that makes the cross-partisan deals in the past difficult. It is this unique political situation, where neither party can hold an agenda long enough to see it through or muddle through status quo governing with the other side in preparation for the next showdown, that is hampering a structure already imperfectly suited to govern a large, heterogeneous society from working satisfactorily.

We added a coda to this core story that is easily forgotten: dissatisfaction with congressional function, if not all of government productivity, pushes people away from engaging with their democratic institutions. I would add that we over-estimate the number of people who are consistently and deeply engaged in politics, especially when the partisan scene is nasty. The people who are left tend to be the partisan warriors, the deeply engaged, and the people strongly committed to issues. Those people tend to be more ideologically extreme, and make demands on Congress that are difficult if not impossible to achieve politically. But they’re the people Congress hears from most.

Those are the core external stories about congressional dysfunction. There’s an equally important story written by Congress itself about how it has turned to self-flagellation to manage the decline in public trust. Starting in the 1990s, when the long period of Democratic dominance finally came to an end, Republican governing majorities signaled the end of the institutional status quo by slashing committee and support agency budgets, cutting back on members’ office allotments, and doing things like sleeping in their offices instead of keeping their pay up to the cost of living. It created a pattern of candidates running against Washington and virtue signaling through their own parsimony toward Congress as an institution that both parties engaged in until the Capitol physically started to crumble. This story is one of a congressional “lobotomy,” where knowledgeable policy staff found it impossible to make a living, the work of member offices shifted to messaging, policy knowledge declined across the board, and lobbyists made up the deficit.

Diving into details

The blue factors on the map are the details contributing to what I just described. Most are still relevant and quite impactful to the current Congress. Instead of going loop-by-loop (which you can do on the Kumu site I embedded above or to a shortened degree on the Democracy Fund website), here are the ones I think are most critical to understanding the current state of the institution:

Increasing leadership control of the legislative process has hamstrung committees, which historically have been the policy engines of the institution. Top-down control also has suffocated members’ ability to work across the aisle on issues where there is alignment. Along with leadership control has come increasing demands on members to maintain partisan loyalty. This area has been the most dynamic since we made the map. Leadership in both parties still aim for swift legislative action with minimal opportunities for members to inject potentially-distracting amendments. They retain a vice grip on what legislation gets to the floor and the time members have to consider bills. They both supersede committee leadership to craft the most substantive legislative packages that move forward. They also both manipulate the committee seating process to reward allies and punish those who step out of line. The bottom line is that very few members of Congress actually matter to what goes on in terms of legislative productivity.

The outcomes of leadership control, however, have diverged for the parties starting in the last Congress. Republican members have been much more willing to act on their frustrations over being locked out of most policy-making processes, beginning with the motion to vacate the chair vote that chased John Boehner completely from Congress as we were in the middle of making this map. Those frustrations boiled over in the 118th Congress, when a rump of the strongest supporters of the Trump agenda seized hold of the nominating process for the Speaker of the House at its organizing meeting until they exacted concessions that provided more power. Unsatisfied that “the uniparty” had changed course, they deposed Speaker McCarthy and have focused on retaking more control of some committees. Speaker Mike Johnson retains significant power to set the legislative agenda, but now must balance it between the White House and its strongest allies.

Democrats, meanwhile, have prioritized party unity over all else, particularly in the House. Democratic leadership did not explore ways to peel off enough McCarthy supporters to isolate the rump insurgents either in January 2023 or during the replacement of him as Speaker. Doing so could have opened up a coalition-style government that would have isolated the hard-core rump, which is using all the institutional leverage it can find to advance unpopular policy proposals (in other words, is trying to win at politics). Democratic leadership continues to prioritize norms like tenure in office, adherence to party line, and fundraising chops to determine committee assignments.

The nationalization of elections and partisan activity has created another set of perverse incentives for members not only to toe the party line, but push the boundaries of partisan messaging. With large, must-pass, leadership-driven bills dominating so much of the legislative calendar, members have little opportunity to accomplish legislative victories for constituents back in their districts. The precipitous decline of local coverage of congressional action means they probably wouldn’t be noticed anyway. The nationalized partisan media and campaign finance landscape offers members an alternative path to prominence via messaging bills and media hits. Conversely, members really do fear primary challenges, even if the research suggests incumbents are typically are extremely safe.

Congressional oversight, which has enormous potential to rectify the problems of modern-day governance, essentially is captured by the agenda setting of the Executive Branch and rarely rises above the level of gotcha politics. The problem is so pervasive few staff have the experience of conducting productive oversight hearings. Their policy, knowledge, meanwhile, is limited by a lack of committee resources and institutional educative capacity.

I’ve written about this before and no doubt will again, but institutional investments in information technology, policy knowledge resources, viable career pathways, and data literacy remain (despite some important wins) a problem with societal implications.

New territory

One of the major reasons I think this systems mapping process was a success for my team is found in the little light-blue dots on the map. Each one represents some form of choice that individuals are making inside the congressional system. Huge political forces may shape and constrain those choices, but we found a lot of individual agency inside the map. Members like to plead helplessness, but they can choose different paths because ultimately, they are the system. Different choices can lead to better outcomes.

That idea formed a major part of the consensus that united the “Fix Congress” cohort in its subsequent work. Even at the start of the 119th Congress, I think it still holds as a theory of change. I don’t think that the institution, as imperfect as it is (looking at you, Senate), is irredeemably broken. I don’t even think it needs to be seeking bipartisan compromise in everything to survive. It can be structured to handle the fights, as long as the sides that lose accept defeat as a valid outcome of the process.

It’s on that point where I think this map is missing an entire dimension. The frustration it captured at its core, for some on the Right, has transformed into position that control is more important than process and that defeat is unacceptable. The debt-limit crisis, which most of Washington simply took as a very hard brand of congressional hardball, should have been a signal when we were creating the map that people in the system were starting to see leverage in not accepting defeat.

Then came January 6th. I was living in Japan at the time and scrambled to put together what had happened while I was asleep. It seems like there was a brief realization that the institution needed to defend itself as a representative body. It was a fleeting one, however, and soon more than 140 members of the House of Representatives — including the co-chair and several members of the Modernization Committee — voted to invalidate the process of choosing a president.

The map may hold, but we’re on different territory now. Democracy reformers still have the urgent task of restoring governing institutions. This process needs to continue, and in as bipartisan a mode as possible, because it reflects an acceptance of the norms and behaviors at the core of democratic life. The second task that has emerged is to isolate and expunge political actors who don’t accept those norms and behaviors and accept only their own power to shape the nation. The most relevant divide today isn’t left-right, but democratic and authoritarian. In this divide, the institutionalists of all political ideologies are on the same side.

As I wrote this last section, the chair of the House Appropriations Committee stated he did not “have a problem” with the impoundment of all federal grants and that what his committee produces is “not a law.” Members have been talking about impoundment for months, but it’s still an absolutely astonishing statement for someone constitutionally at the center of Legislative Branch power and an ominous one that the entire institution might just roll over. Even with the warnings of the last four years, I’m not sure the democracy reform field is prepared conceptually for what has changed.

If you’ve read this far, you might be the type of person for this message: some of my motivation for writing this substack is to attract the attention of foundations and nonprofits who may need a consultant like myself. If you have need for organizational strategy, writing/editing, research, or grants portfolio help, please reply to this email or nowwhatnehls@substack.com and I’ll reply via my personal email.